4.2.2. Parsing¶

Now that we have the hacky solution, let’s see what a nicer solution would look like.

One problem that our hacky solution had was that it made fairly strict assumptions about the input data. For example, in dot, as the semicolon is the delimiter between statements, it’s not necessary for the left hand side and the right hand side of an arrow to be on the same line. That means, e.g. the following file is a valid dot file:

digraph dep2 {

A

->

B

;}

If given to dot, it would display a graph showing an arrow from A to B as expected. But our hacky solution would be unable to parse this. Furthermore, it could be fairly non-trivial to improve our solution to work on all dot files with different formatting. For this, proper parsing is necessary.

4.2.2.1. Grammar¶

Now, parsing means turning an input (text) stream into a data structure. We did this in our hacky solution, but another attribute of parsing is that the input is parsed according to a certain formal grammar. Grammar is often described using the Backus-Naur form (BNF). We could define a grammar for the subset of dot files we want to parse using Backus-Naur form by e.g. the following:

graph ::= "digraph" characters '{' statements '}'

statements ::= '' | statement statements

statement ::= label | edge

label ::= characters labelname

labelname ::= '[' "label" '=' quotedstring ']' ";"

quotedstring ::= '"' labelstring '"'

labelstring ::= characters | ' ' labelstring | characters labelstring

edge ::= characters "->" characters ";"

characters ::= '' | 'a-zA-Z0-9_-' characters

This defines the formal grammar for our dot files recursively. For example:

- A graph is parsed when the following is encountered: the string “digraph”, followed by characters, followed by the character ‘{‘, followed by statements, followed by the character ‘}’

- Characters is defined either by nothing, or any printable letter from the English alphabet, or a digit, or an underscore or a hyphen (‘-‘), followed by characters

- Statements is defined either by nothing, or a statement followed by statements

- A statement is defined as either label or edge

…and so forth. (Note that the above strictly speaking isn’t valid BNF as for example the regular expression-like definition in characters isn’t included in the original BNF definition. Many variations of the original BNF are used in practice.)

Exercise: The Graphviz project also document the full grammar for the dot language. Look it up online.

4.2.2.2. Lexing¶

Now that we have our grammar defined, we can almost start writing the actual parsing code. However, if you try this you’ll see it’s more difficult than you’d expect: there’s a lot of state to keep track of when going through your input file character by character. For example, if you encounter a quotation mark (“), you need to note that you’re now inside a quoted string. If you encounter a character, you need to know whether you’re parsing a graph, or the “digraph” word of the graph, or the name of the graph (characters), etc. Writing a parser this way can become cumbersome very quickly.

A way around this is to split one part out and preprocess the input: lexical analysis or lexing first turns the character-by-character input stream to lexemes or tokens which are much easier to work with when parsing. In our case, the following could be our tokens:

- The word “digraph”

- characters (an identifier)

- The character ‘{‘

- The symbol “->”

- A quoted string

- Etc.

After the lexical analysis, instead of handing our parser a list of characters, we hand it a list of tokens. Then, our parser needs to check that the input tokens are correct and store the data in the correct data structures as necessary, making this a much easier task.

How would we start? We can first define tokens as an enumeration:

class Token(object):

EQUALS = 0 # the character '='

DIGRAPH = 1 # the word "digraph"

IDENTIFIER = 2 # characters

QUOTE = 3 # quoted string

OPEN_CURLY = 4 # the character '{'

# and so forth

Now, when reading in a text stream, how would we know whether we’ve encountered a token? With a regular expression! Furthermore, as we learnt in “PNG files”, we can apply data driven programming by defining a list which defines a regular expression for each token:

tokens = [(re.compile('='), Token.EQUALS),

(re.compile('[ \n\t]+'), None),

(re.compile('digraph'), Token.DIGRAPH),

# and so forth

Here, we define a list with the following characteristics:

- The first element in the tuple for each element in the list is a regular expression: this may either match or not.

- The second element in the tuple describes which token the regular expression should generate when it matches. Note that we also parse whitespace but don’t associate it with a token. This way we can consume all whitespace out of the way.

Now that we have our tokens defined we can start with the lexical analysis:

pos = 0

lexer_output = list()

while pos < len(input_stream):

for regex, token in tokens:

# TODO: check for match with regex

In the above snippet, we have the input stream as a string which we can slice like a list, we want to output a list of lexemes, and have an integer (pos) to track the current position in the input stream. We can do this:

- Use input_stream[pos:] as the input - that is, the string after cutting out the first pos characters

- Loop through our possible tokens and use re.match() to apply a regular expression to the input

- If we have a match, store both the token and what was matched in lexer_output. We need sto store what was matched so the parser has the necessary information required for parsing later on. You can retrieve what was matched by running result.group() whereby “result” is the return value of re.match().

- After a match we can advance position by the length of what was matched

- If none of the tokens matched we should raise an error

Exercise: Finish and test the lexer. If you prefer you can start with a simpler form of dot files first, i.e. without labels but instead only the “A -> B;” form.

4.2.2.3. Data structures¶

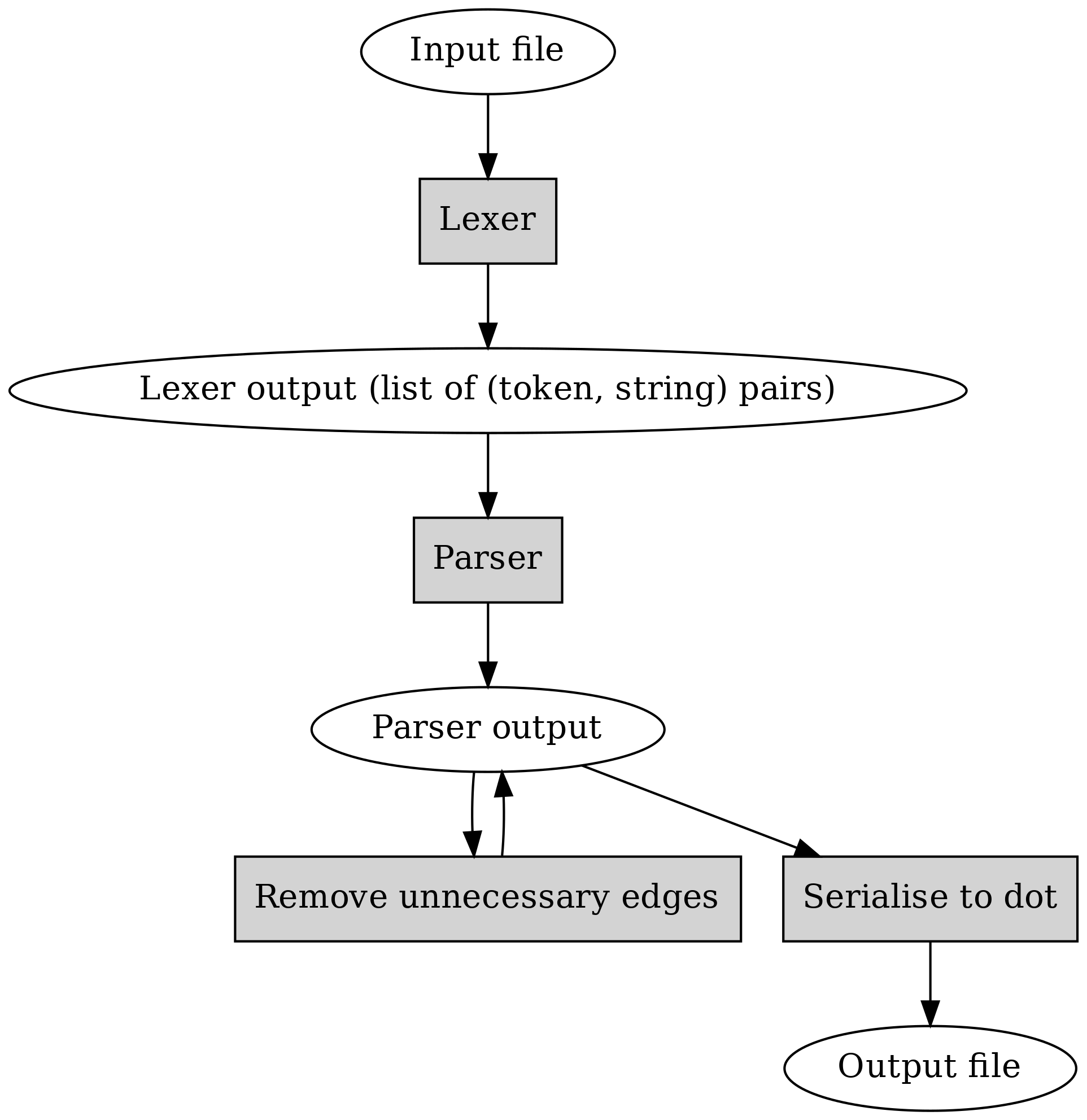

Now that we have our lexer output, we could parse it. Overall we’d like to have the following data flow:

Here, one thing to note is that the parser output format should be something where we can remove unnecessary edges, and use for generating a dot file.

In terms of code, the high level view of using this could be e.g.:

lexer_output = lex(input_filename)

p = Parser(lexer_output)

p.parse()

p.graph.simplify()

print p.graph

Hence we should store the output of our parsing in data structures and we should define these first. Classes seem like a good way to do this, and our classes should also somewhat reflect the data that we can expect to find in our dot files. This means we can be inspired by our grammar definition when defining our classes. E.g.:

class Graph(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.statements = list()

class Label(object):

def __init__(self, name, label):

self.name = name

self.label = label

# TODO: include other necessary classes such as Edge

Exercise: Implement the necessary data structures for storing the parsed data.

4.2.2.4. Parsing¶

Now we can finally actually parse our lexer output. We need to write a loop that goes through the list, keeps track of the current state, i.e. what’s expected, checks the input for validity, and stores the parser output to data structures.

Exercise: Give this a try. Don’t worry if it doesn’t work; the next section will provide help.

Now, when writing a parser, there are several patterns that come up. For example:

- Getting the next token

- Checking whether the next token is as expected

- Extracting information from a token; for example, a token holding characters may be an identifier which we want to store as the name of a graph

It’s often helpful to write helper functions for these. Furthermore, it may clarify the code to have the parser state like how far the parser has progressed by having this state stored as member variables of a class. One could then use the class e.g. like this:

p = Parser(lexer_output)

p.parse()

# p.graph would hold the parsed data

The parser you wrote at the previous exercise may work but you may be able to make your code cleaner by restructuring it e.g. as follows:

class Parser(object):

def __init__(self, lexer_output):

self.lex = lexer_output

self.pos = 0

self.token = self.lex[self.pos]

def next(self):

self.pos += 1

if self.pos < len(self.lex):

self.token = self.lex[self.pos]

def match(self, char):

if self.token[0] != char:

raise RuntimeError('Expected "%s", received "%s"' % (char, self.token))

self.next()

With this, writing the parser becomes relatively simple as we need to use our primitives to progress through the input, e.g.:

def parse(self):

self.match(Token.DIGRAPH)

name = self.identifier() # TODO: implement

self.graph = Graph(name)

self.match(Token.OPEN_CURLY)

self.statements()

self.match(Token.CLOSE_CURLY)

def statements(self):

while self.token[0] != Token.CLOSE_CURLY:

name = self.identifier()

if self.token[0] == Token.OPEN_SQUARE:

self.match(Token.OPEN_SQUARE)

self.match(Token.LABEL)

# TODO: write the rest

elif self.token[0] == Token.ARROW:

self.match(Token.ARROW)

name2 = self.identifier()

# TODO: write the rest

else:

raise RuntimeError('Expected statement, received "%s"' % self.token)

Now we can write the rest of the parser.

Exercise: If your parser didn’t work after the previous exercise, make it work using the code snippets above. Also try giving it some invalid input.

Now, if all has gone well, we have the contents of the dot file in our data structures and can proceed with the following:

- Remove unnecessary edges using the algorithm from the previous section

- Serialise our data structures to a dot file, i.e. write out the contents of our data structures in the proper format

Exercise: Write a member function of the Graph class that removes unnecessary edges and test it.

There are a few ways we could serialise our data. Ideally we’d be able to do this:

g = Graph(name)

print g # this statement writes out the graph as a dot file to stdout

How “print” works in Python is that it calls the member function __str__ of your class, expects a string as an output of that function, and then writes that output to stdout. We can define this function e.g. like this:

def Graph(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.statements = list()

def __str__(self):

ret = 'digraph %s {\n' % name

for s in statements:

ret += str(s) + '\n'

ret += '}'

return ret

Now, all we need to do is define __str__ for all our classes.

Exercise: Serialise your data to a dot file by implementing the necessary __str__ member functions. Tie everything together by lexing and parsing the input dot file, removing unnecessary edges and serialising the output. Check that the output matches the output of the previous section.

Congratulations, you’ve now written a parser. More specifically, this is a top down parser as it parses the top level data first before proceeding to further levels. Even more specifically, this could be a recursive descent parser because our grammar is defined in a recursive manner (e.g. characters), though in practice your implementation probably doesn’t use recursion as our lexical analysis merged tokens such that no recursion during parsing is necessary.

Parsers are fairly common in that they’re part of the implementation of compilers, interpreters including for languages such as Python and JavaScript, HTML renderers, regular expression engines, editors (syntax highlighting and indenting) and more. As such, during this book we’ve already indirectly used several different parsers.

Another tidbit is that the formal grammar we defined is a context free grammar which has an interesting mathematical definition but in practice means, among other things, that one can define the grammar in BNF form. Context free is opposed to context sensitive grammar where context matters; tokens before or after a token determine what the token means. For example parsing the C language is context sensitive because e.g. the asterisk (“*”) may mean either part of a pointer variable declaration, pointer dereferencing or multiplication depending on context.

A subset of context free grammars is a regular grammar. A language described by a regular grammar is called a regular language. A concise way to describe a regular language is by using a regular expression. In other words, a regular expression like e.g. “[a-z]+” is, like BNF, a way of defining a formal language (in this case one or more lower case letters), and evaluating a regular expression is equivalent to parsing a string with the regular expression as the grammar and returning whether the input conforms to the language or not.

Because regular grammar is a subset of context free grammars, context free grammars generally cannot be parsed using regular expressions, similarly to how context sensitive grammars generally cannot be parsed using context free parsers. (This grammar hierarchy is also known as Chomsky hierarchy.)

Exercise: Is it possible to parse HTML with regular expressions?