4.1.5. Unix way - sched¶

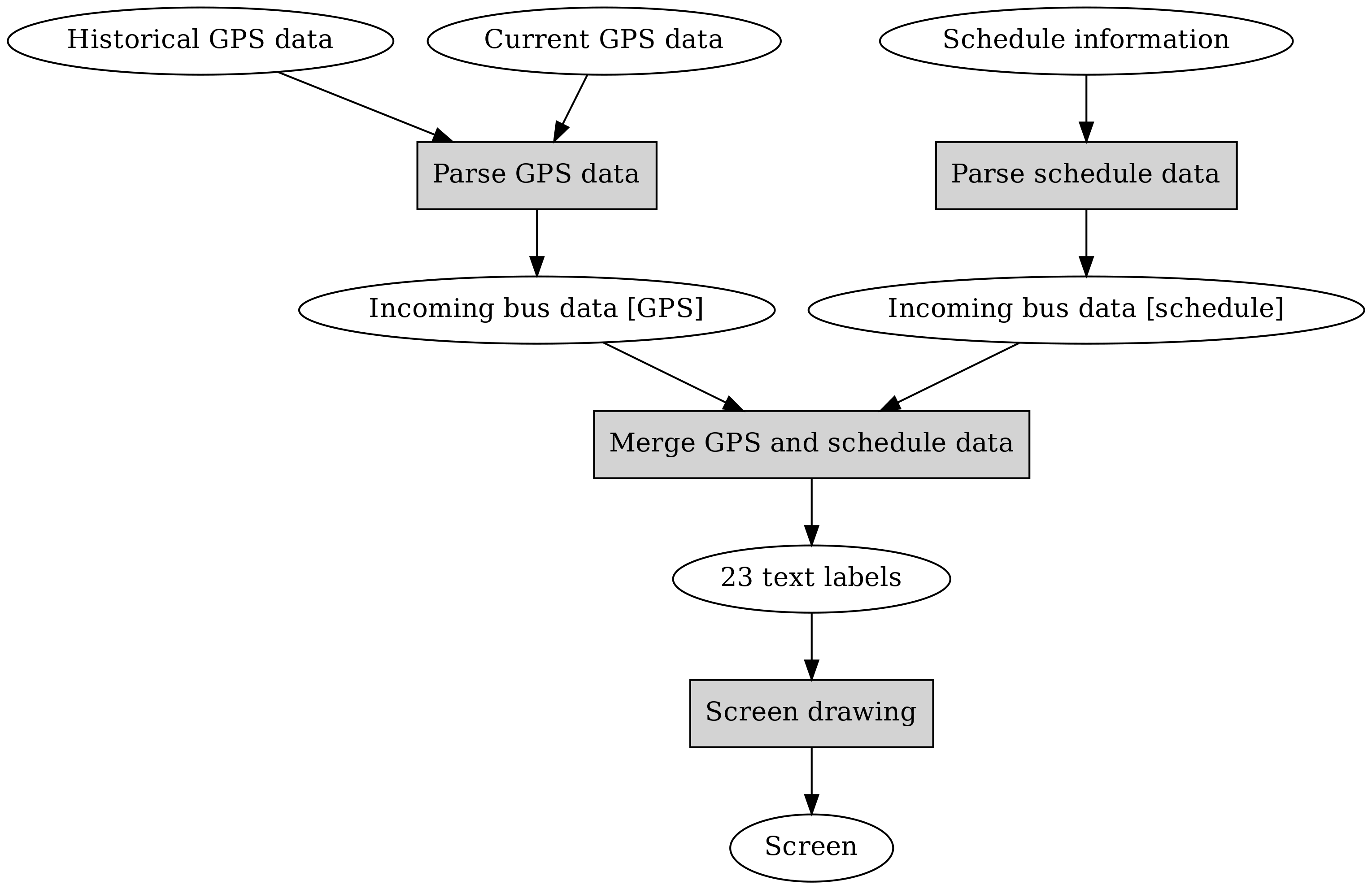

We now have a C++ program that can display labels provided in a text file. Let’s take another look at our high level architecture:

Furthermore, let’s implement the Unix way i.e. engineering spec 1 first.

The input to our screen drawing program should be given by a program called “merge”. However, “merge” requires incoming bus data which we don’t yet have so let’s implement the programs to generate this data from the original input i.e. schedule information and GPS data first.

4.1.5.1. sched¶

As per the requirements document, the schedule information, which is the input to sched, will look like the following:

3 1 5 6 3 2 5 16

Here, the numbers are the route number, the start number, and the hour and minute of the bus arrival according to the schedule.

As per our engineering spec, the output of sched should look like the following:

3 1 5 6 1 3 2 5 16 1

In other words, the output format is exactly the same but with a 1 appended at the end to signal the fact that this data point is from a schedule, which is needed when merging the predictions based on GPS data with the schedule information. The tricky bit about sched is that it should only output the next (up to) 50 buses arriving based on the current time which is also given to the program as a parameter. So if e.g. the time 5:10 was passed to sched, it shouldn’t output any buses arriving before 5:10.

We can put together a simple test case so we can see whether our program works as intended.

Exercise: Create a test input file for sched. It should have the input format as above and include e.g. five lines for five buses. The buses should have different arrival times so that if you had a functioning sched and passed a time and your test file to it as input, you could see whether that the buses that according to schedule have already passed wouldn’t be included in the output.

Now, let’s implement this program and try it out. Here’s what our program will need to do:

- Parse command line arguments and note the given time and filename

- For all entries in the given file, filter out the entries that are in the past

- Sort the remaining entries by time and retain the 50 first ones

- For all the entries, print them out to stdout in the given format

4.1.5.1.1. Command line arguments¶

Accessing command line arguments in Python can be done using the sys.argv list:

import sys

def main():

num_args = len(sys.argv)

print 'we have %d arguments' % num_args

for arg in sys.argv:

print arg

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Here we introduce a couple of concepts:

- We import ‘sys’ and use the sys.argv list to access the command line arguments to the script

- We put our code to a function called main. In our toplevel code we check whether the special, built-in variable called __name__ equals ‘__main__’. If it does, this means the user has executed the program directly as opposed to importing the file from another Python script. Structuring the code like this makes it possible to use as a library which will become useful later. If the program was executed directly we call the main function which does all the real work.

4.1.5.1.2. Working with bus schedule entries¶

One potentially tricky thing is finding out whether an entry is in the past or not. How would you go about it? Have a think.

What we have is two time stamps, both having two integer values (hour and minute). The first one is the current time while the second one is the time stamp of an entry. We need to find out whether the second one is before or after the first one.

Now, because the time of day is circular, a time stamp can be said to always be after another one: it could just be 23 hours and 59 minutes after. We can break this cycle by agreeing e.g. that only the entries 12 hours after the current time are actually considered to be in the future. We should also ensure we handle midnight correctly such that e.g. the time 00:02 is treated as after 23:58; we want the bus schedule display to show buses travelling right after midnight even if it’s right before midnight.

We can use this to put together a small test suite:

- First parameter: 06:34; second parameter: 06:40; return value should be 6

- First parameter: 06:40; second parameter: 06:34; return value should be -6

…and so forth. We can formalise this in Python:

def test():

assert diff_time((6, 34), (6, 40)) == 6

assert diff_time((6, 40), (6, 34)) == 6

assert diff_time((6, 56), (7, 14)) == 20

assert diff_time((7, 14), (6, 56)) == -20

assert diff_time((7, 14), (9, 30)) == 136

assert diff_time((9, 30), (7, 14)) == -136

assert diff_time((23, 58), (1, 12)) == 74

assert diff_time((1, 12), (23, 58)) == -74

Here, the function diff_time is our function to implement. It takes two parameters, each being a tuple of two integers. This is a unit test: it tests the code of one unit in isolation of others and can be used to ensure that a function performs correctly.

On the implementation of diff_time itself, “all” that it needs to do is take into account that an hour is 60 minutes, and track which time is bigger. It might be useful to think of it such that the timestamp can be converted to a number of minutes passed since midnight, so that e.g. the time 6:00 is represented as 360 (6 * 60) minutes, making the comparison easier.

Exercise: Implement the function diff_time which shall return the number of minutes the second timestamp is ahead of the first timestamp. Use the above test suite to ensure correctness.

In the above, the timestamps were represented simply as tuples. It might be clearer to represent a timestamp using a class instead, such that the class has two member variables, i.e. hour and minute. Feel free to refactor your code to use a class instead if you prefer.

Now that we’re able to parse command line arguments and we have the diff_time function, and we have some understanding of sorting and slicing lists in Python as well as printing out values, we can tie everything together. The final program should e.g. behave as the following:

$ ./sched.py 5:15 sched_test.txt

3 2 5 16 1

3 3 5 26 1

3 4 5 36 1

3 5 5 46 1

That is, the time should be given in hh:mm format, and the output should be written to stdout. Here, the bus arriving at 5:06 is not output despite it being present in sched_test.txt.

As a reminder, here are some building blocks to get you started:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | def main():

argument = sys.argv[1]

after_split = argument.split(':')

hour, minute = after_split

hour_as_int = int(hour)

entries = list()

with open(sys.argv[2], 'r') as f:

for line in f:

# TODO: parse line here

entries.append((route, startnr, time_diff, hour, minute))

entries.sort(key=lambda (route, startnr, time_diff, hour, minute): time_diff)

for (route, startnr, time_diff, hour, minute) in entries[:50]:

print route, startnr, 1

|

The above snippet demonstrates the following:

- Argument parsing (lines 2 and 7)

- String parsing (line 3)

- Tuples (lines 4, 10, 13)

- Converting string to int (line 5)

- Reading a file (lines 7 and 8)

- Appending to a list (line 10)

- Sorting using a callback (line 12)

- List slicing (line 13)

Exercise: Tie everything together to read a test schedule file and output the next schedules buses. Once you’re done, test with the full sched.txt file that was available for download a couple of sections back.